The Reflective Observing Method – Using Smart Telescopes to Experience Big History

- jsweitzer6

- Jan 1

- 13 min read

Introduction

I must first confess guilt for not entering anything new on this site in about a year. Actually, I have visited it to share posts when people have questions about smart telescopes that I’ve already written about. But I haven’t made any new entries since last February when I reported on my visit to the Shanghai Astronomy Museum. I have stayed on the trail of smart telescopes and been working on envisioning their use for education in particular. I have worked on plans for a Smart Observatory programming for a new astronomy center in New England.

When I have found myself online periodically addressing questions by newbie smart telescope (ST) users. I sometimes find myself trying to keep from giving snarky answers to questions like: “Am I seeing the disk of the star Sirius in this burned-out image?” or “Can I image the entire band of light of the Milky Way?” Why some novices waste their time imaging bright stars I’ll never know. And, I hope and pray in the New Year that all users get to know the field of view of their scope in degrees and its basic resolution in arc seconds. This will all come with time and studying.

My blog inactivity is going to end now. I’ve gassed it back up and am ready to go. So, what have I been up to in order to explain myself? At one point I thought I’d just wait for T Coronae Borealis to blow up and then I’d jump back in with my reflections – but ha! That might not happen for a thousand years -- so much for the online astronomy hype. I’ve seen my ways, however, and will aim to relate astronomy to Big History, if that makes sense, in a Universe “only” 13.8 billion years old. In fact, all cosmologists and astronomers have been doing Big History. But now the term includes all of human history, biological evolution and Earth’s geologic history as well.

I have been keeping busy scientifically with background research in physics and astronomy. I gave presentations on “The Journey of a Photon” and “The Vera Rubin Observatory (VRO).” Those were much more work than I’d thought they’d be. They had good spin offs, however. The first one has caused me to jump back into my quantum mechanics education and ramp up on quantum field theory. (BTW, 2025 was the 100th anniversary of the “birth” of Heisenberg’s crucial step in the revolution in quantum mechanics this year.) The second was a great chance to immerse myself in the life of Vera Rubin (whom I’d once served on a committee with) and start to help the educational programs connected to the first light for the Siminoyi Survey Telescope (SST) at the VRO. For much of this year I told people that the VRO’s SST was my “new” telescope. They laughed because they know I’m dedicated to my smart telescopes.

I have observed when I can. The weather has been rather cloudy this past year and even when it was cloud free during the summer here in the Chicago, we were once again plagued by smoke from wildfires in Canada. I am a member of the Climate Reality Project, so I know it’s ultimately a CO2 problem. Unfortunately, I have to be quite pessimistic that that’s going to be solved soon. Although I actually used my Vespera to help promote solar energy at an event in September and I will continue to advocate for sound energy policies, I’ve grown a bit pessimistic and am just trying to cope now – especially as it affects my observing.

Oh, and there’s one more part to my absence and motivation to get back to the blog. It has to do with Image Processing – or rather my laziness. I’ve watched the many outstanding results people with smart telescopes are getting with new, polar aligned scopes, large numbers of stacked images, and amazing software. I have great respect and admiration for the results of those who work very hard to harvest reams of photons, distill them carefully and craft them into wonderful images. (See one of Mike Jones efforts below.) But, although I do know a bit of Photoshop and have tried Pixinsight, I just don’t have the patience or appetite for extensive Image Processing (IP). Part of it might be because my limited access to the sky makes it difficult for me to do long integration times. Maybe if I’d lived in a less cloudy and wooded location free of Boreal Forest smoke I would, but alas I do not. I also sold my Seestar S50 to a friend who coveted it. It was great, but the other four telescopes I have are enough. It’s also not that different than the Vespera.

In this image, Mike used his Vespera2 with a dual band filter to take 1,700, 10 second subs. This comes to nearly 4 hours. The final image data were processed in Pixinsite and Photoshop.

(As I’ve been writing this blogentry I just learned of the app AstroEdit. It actually looks pretty good and is less than $3. I’ll try it and get back to you.)

My greatest interests in astronomical observing are different than the that IP Way as I call it. I refer to it as the Reflective Observing Way, or just RO. I hope to show you how smart telescopes are perfect for the RO. The goal of this current blog entry is to explain what I’m exploring as I am currently finding my way among the heavens. Maybe others might of you like it too? I’ll also show how RO aligns well with another type of ancient thinking that some Romans liked too.

Reflective Observing is the term I use for making the experience of attending to observing using a smart telescope into a mentally active process. It’s not for using one’s telescope on automatic mode overnight or remotely. It can certainly work for traditional telescopes but I find it’s especially enjoyable with my smart telescopes.

The active Smart Observer “asks” four questions about the object they are observing:

1. What am I observing? This involves knowing what kind object it is and how it’s emitting the light that we detect. One can and should go farther into understanding how this type of object fits into the broader story of cosmic evolution. For example, is it a star forming region or a dying star? Is it a cluster of stars or an entire galaxy of stars? Could it be harboring planets? All of this should basically be researched before heading outside. I have long been a proponent (probably because of my planetarium background) of my often saying:

You can’t understand what you’re seeing unless you have a mental model of what it is.

2. How far away is it? This is pretty straightforward. Look up the distance in light years ahead of time. There will be slight differences in the quoted numbers for sure, but pick the best one you know. Once you have the distance you must also get an idea of the scale of the field of view you will have. By that scale I mean how wide is the scene you’re looking at the distance of the object. This too doesn’t have to be super precise for RO…. For example, I know that my eVscope has a field of view of about 0.5 degree. This describes a small triangle in which the base of the triangle is about 1/115 or about 1% of its altitude. Here’s the formula you can use for your scope…

Let D = distance to the object.

Let W = width of the scene at the distance of the object.

Let FOV = field of view of the telescope.

D/W = 0.5 x cotangent (FOV/2)

Below I will talk about a galaxy 30 million light years away. Dividing this by 115 I get a scene width of 260 thousand light years or about 2.5 times the diameter of our own Milky Way galaxy.

3. What would be happening on Earth if we could see it from the object? This has been traditionally called the View from Above, as we’ll see later. This I consider the most important part of the process to try and ponder while watching the image “develop.” To do this you will have to do your homework ahead of time. I often just use Wikipedia, but there are also nice time charts in David Christian’s book, “Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History.” If we just use the Messier Catalog, we can experience time scales from that of the Pleiades (M45) at 445 light years to M109 at 68 million light years. These times span from Sir Francis Drake’s first circumnavigation of the globe to the Chicxulub Impact – the asteroid that ended the reign of dinosaurs and the rise of mammals, of which I am one. I happen to enjoy natural history as well as prehistoric history and pretty much any form of history. So, doing this history background is fun and personal that’s why if each of us compiled a list of events connected to Messier Object light travel time distances we might come up with different events – at least for the more recent times.

4. How might I describe or sketch it? My science education background also leads me to always want to do something with what I’m learning. It’s hands-on if it’s something we can experiment with, but in this case minds-on too. I love drawing and painting, so I try to make a sketch of what I’m seeing. It doesn’t have to be accurate, although it could if you are astro artist. I love seeing what people can sketch. It also doesn’t have to be directly representational either. Certainly, astronomy is a great source of abstract images or even micro-constellations. Mine are pretty rudimentary, but I have fun with them. Sometimes I have gone back over them later with water colors.

So why are smart telescopes (STs) good for reflective observing?

First of all, Deep Space Objects, located from dozens to millions of light years away are easy and recognizable in ST’s. Not that one couldn’t with a good sized (read bulky and heavy) Dobsonian in a moderately dark site (read get in the car, drive far from home and hope the weather cooperates), but that’s just too hard to engineer for most people. Unlike the planets or the Moon, there are always deep sky objects one can image with a smart telescope. Not all are as beautiful as M51, but all, without exception are interesting intrinsically, and in terms of the stories they can help tell, either their own or the View from Above they present.

Second, the process of image stacking make a 15 to 30 minute session interesting visually. Sometimes that’s all the time I have or if I do have more, it’s not a lot. Luckily, 30 minutes will bring out much of what one needs. In addition, ST’s reveal their images in a non-fatiguing way on smart phone or tablet apps. The light is strong enough that using a red headlamp and a small sketch book one can sketch easily what one is seeing. If I were to sketch through one of my optical telescopes, I’d have to make sure I could look in the eyepiece at the right angle and height. And juggling any sketch book might be harder. Now, I do very much like and advocate eyepiece viewing, but it’s not necessary for reflective observing.

I do have a little video screen with an eyepiece on my eVscope which I often use, but I’m not restricted to it. A big part of my interest in eyepieces, which I’ll deal with in a future blog, are the fact that they create an immersive experience that small screens just don’t. I have actually developed a viewer to try and duplicate the experience with my phone, but it still needs debugging before I write about it.

One final thing I like about the reflective observing of deep sky objects is that to understand them even at a basic level, one really needs to know some basic astrophysics at the Astro 101 level. I’m taught that course but as an educator think that the STs now become a great motivator for owners to brush up on their astrophysics or work on filling in on it.

A Reflective Observing Example: NGC 891

For my first example, I thought I’d try NGC 891. It’s a beautiful edge-on spiral galaxy that does well in my eVscope’s field of view. (Those of you old enough to remember or who stream the “Outer Limits” television show of the 1960s will recognize it as the galaxy in the credits.) So, on the Sunday just before Thanksgiving it was beautifully clear and not too cold in my Chicago back alley. I did some quick homework to make sure I had the scale and distance to the object correct: 30 million light years distant and some 110,000 light years in diameter about the same size as our Milky Way. I know what edge on galaxies are, so I didn’t have to do the astronomy background. For example, just seeing the obscuring darker band says that there are interstellar dust clouds which necessarily came from earlier generations of stars and probably systems with earth-like planets.

I had pre-adjusted my telescope’s tripod legs so that I could easily look through the eyepiece from my little folding chair. I also set up a little table between my legs with my phone on it and propped to be easy to see. I put my red headlamp on and got out a little sketch book. I let the imaging go for over 20 minutes. The image is pasted in above and it was not processed, this is just how it looked in my eVscope and on my phone.

As the imaging was stacking more and more 4 second exposures, I first reflected on the fact if I were instantly transported there and looking back to Earth then I would be detecting photons that were 30 million years old. Here are the two events on Earth I reflected upon:

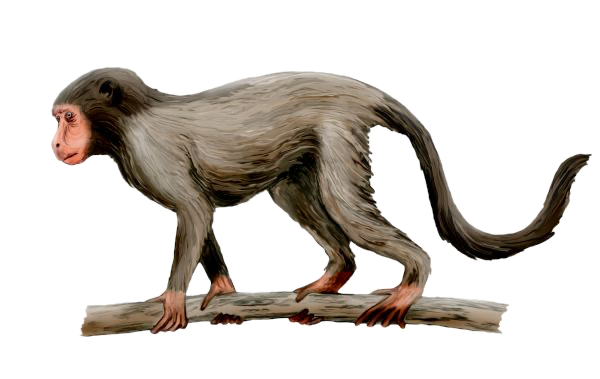

Back then on Earth, the primates were evolving into a line that would eventually lead to great apes like us. I believe our earliest, “ancestor” back then was just like Aegyptopithicus, pictured below. Primates were also, around then, branching out into the New World. Color vision was just starting to get going in our Old World ancestors at that time too.

Back on the ground at 30 million BC, the Alps as we know them in the picture below were rising to be what we see today due to the collision of geological plates.

While I was observing and reflecting, I sketched what I was seeing as the image gradually improved over 24 minutes. I was pleasantly surprised that my iPhone adjusted its brightness in response to the red headlamp and the entire process was pleasant. My sketch is below.

I call this entire process Reflective Observing. In thirty minutes, I not only peered 30 million light years into space to see a galaxy much like our own, but also had an overview experience of life back on earth. So why do I consider this process considered Roman? It’s in good part because of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius.

Conclusion -- “View from Above …” Reflective Observing the Roman Way

Marcus Aurelius was a well-known philosophical stoic. In addition to overseeing the Roman Empire from 161-180 CE, he practiced stoicism and wrote about it routinely. I believe he only meant the writings to be private and so they are called Meditations.

One perspective of the stoics resonates well with astronomers and those of us inspired by the views of the Apollo astronauts for example. (BTW As I’m writing this it’s the 57th anniversary of the Apollo 8 mission when the first picture of the entire Earth from space. Some have called the reactions of astronauts the Overview Effect.)

The Stoics would have called it the View from Above.

Watch and see the courses of the stars as if you were running alongside them, and continually dwell in your mind upon the changes of the elements into one another … When you are reasoning about mankind, look upon earthly things below as if from some vantage point above them.

Marcus Aurelius, Book 7, Secs 47-48

But in my view, I try to look upon earthly things from above, but by looking at deep space objects and using them as if they were time machines into the Earth’s past. Reflective Observing is also an attempt to situate us as the product of a long line of events dating back to the earliest history of the universe.

The ultimate idea is to make us feel our tiny and humbling role in the universe. If learning astronomy does anything, it does make us small in space and time. But, I also think it can be reassuring in some ways make use “big” by underscoring the fact that we are part of the amazing process of the universe, and that we are now doing pretty well figuring it all out.

Reflective observing requires preparation. Here are the steps I take.

1. Practicing this type of observing requires preparing one’s mind before heading to the telescope. I carefully pick the object I will observe based upon what I know I can get 30-60 minutes of observing before the sightline runs into a tree or building.

2. Before heading out, I usually read about the object either online or at least inn one of Stephen James O’Meara’s, Deep Sky Companions, like: The Messier Objects, 2nd Edition.

3. The astrophysics is relatively easy for me since I’ve studied it my entire life. If you don’t know an HII region from a globular cluster or from a planetary nebula, I recommend that you be sure of what you’re looking at too. A good Astro 101 text will do and it can be free. Check out this one: https://openstax.org/details/books/astronomy-2e

4. I then do the light travel time calculations given the distances involved in light years.

5. To get a handle on what’s happening back on Earth at the time the light left the object, I either consult Wikipedia for historical guides, or I have recently been looking at a text book for big history, which also deals with pre-historic and pre-archaeological evidence. This text is David Christian’s, Maps of Time – an Introduction to Big History.

6. I take out a sketch pad or card. Not big mind you, but easy to hold in one hand. I have a head lamp that goes red. I use pens – black or increasingly white on black card stock.

7. Finally, my phone has an attached bracket to set it at an angle. I am considering using a small angle mount too. I then set this on a small table I use.

8. When observing and sketching I do the following:

a. Stars first

b. Stipple to bring in the DSO, if it is unresolved

More reports on reflective observing will be coming from me in 2026. I promise to jump in when I can help with general concept clarification for new ST users. I also assure you I will try to be briefer. Thanks for your attention.

Happy New Year and wishing you lots of clear weather just when you need it most.…

I love your "reflective" observing method, right down to the double entendre in the name. (This, despite the irony that smart telescopes are all refractors!) In keeping with these artificial intelligence times, I've tried to make my SCT artificially smart. The Pegasus SmartEye was supposed to do that, but not in my SCT (apparently too long a focal length to do live stacking). I've been toying with the Celestron Origin, the biggest aperture and perhaps the fastest optics among all the smart telescopes. Would be nice to get your thoughts on how the Origin, uh, stacks up.